Reverse Engineering EVM Storage

Ethereum storage is deceptively simple: 32-byte slots holding 32-byte values. But mapping those slots back to meaningful variable names is where things get interesting. Particularly when the goal is to go beyond generating a simple layout to reverse engineering SSTOREs within transaction traces. This was my objective with SlotScan.info, and forms the background for the learnings that I will share here.

Example "Transaction" view from SlotScan.info

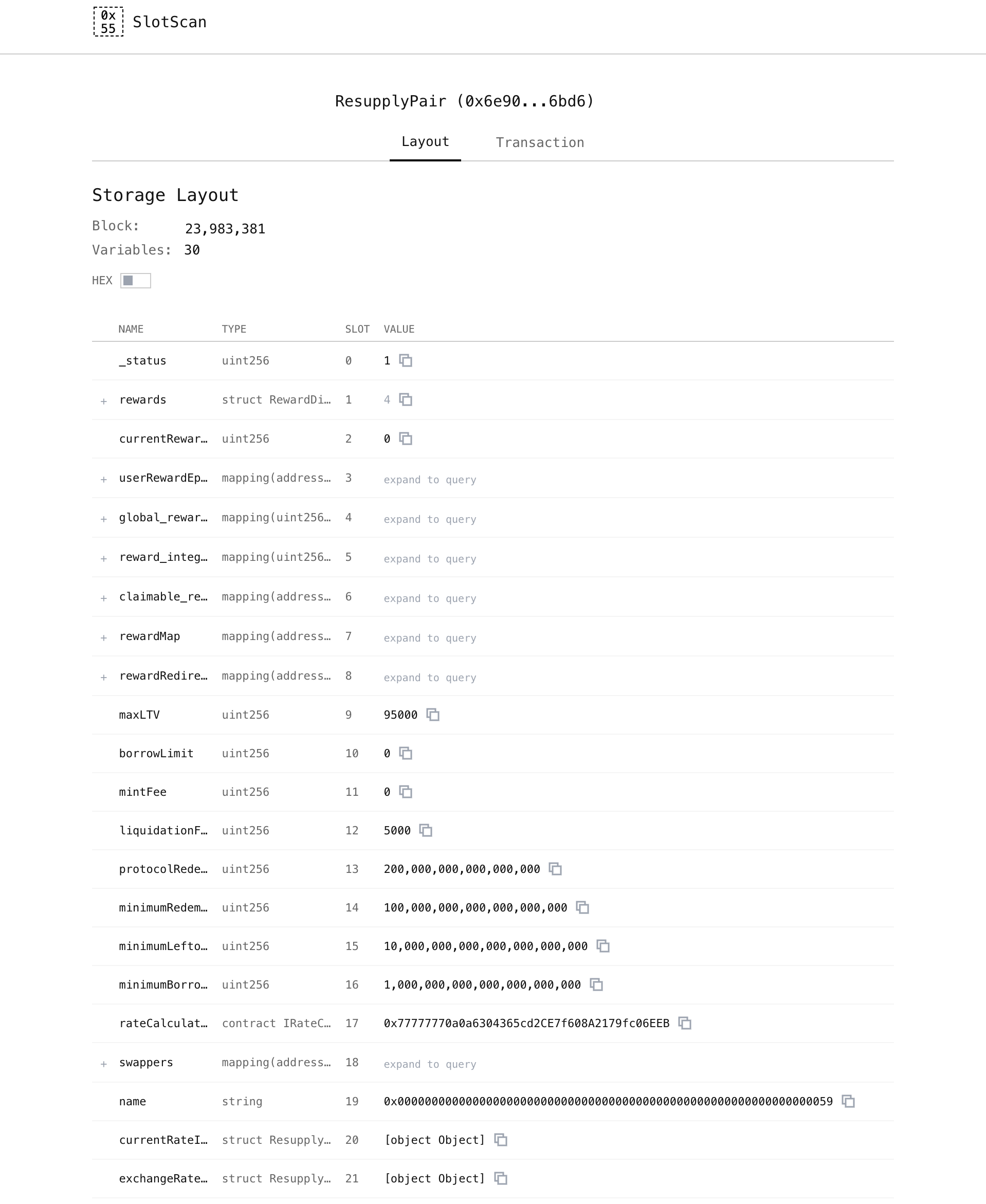

Example "Transaction" view from SlotScan.info  Example "Layout" view from SlotScan.info

Example "Layout" view from SlotScan.info Contents

- Background

- Tracing Transactions

- Resolving Mapping Keys

- Decoding Storage Patterns

- Proxy Detection

- Storage Layouts

- Edge Cases

- Key Takeaways

- What I Built

Background

The EVM has no concept of variable names, types, or struct members. That information exists only in compiler metadata. And since mapping slots are computed as keccak256(key || baseSlot), you’re dealing with one-way functions: given a slot hash, the key that produced it is mathematically unrecoverable.

This post covers the techniques I learned and utilized to reverse engineer EVM storage: capturing hash preimages at runtime, decoding complex storage patterns, tracing transactions through DELEGATECALL chains, and detecting proxies.

Tracing Transactions

To decode storage changes within a transaction, I need three things:

- What changed: Which slots, with before/after values

- Mapping keys: The preimages that produced hashed slots

- Write order: The sequence of changes (a slot might be written multiple times)

No single RPC call provides all three. Here’s the approach I landed on.

Ground Truth: prestateTracer

debug_traceTransaction is an RPC method that replays a transaction and returns trace data. With the prestateTracer option (in diff mode), it returns a compact summary: exactly which storage slots changed, with their before and after values.

This is the ground truth for what changed. But it only shows the final state. If a slot is written three times, you only see the first and last values.

Execution Order and Preimages: structLogs

For the full picture, I need the execution trace. structLogs is a trace format that returns every EVM step: the opcode, stack, memory, and program counter. From this, I extract:

- SSTORE operations in execution order (capturing intermediate writes)

- SHA3 operations with their memory inputs (the preimages for mapping slots)

The SHA3 capture is critical. When the EVM computes keccak256(key || slot), the preimage sits in memory. I grab it before the hash is computed, building a lookup table of hash → preimage.

Why Both?

prestateTracer is authoritative but loses intermediate writes. structLogs captures everything but is massive (a complex transaction can produce a 2GB+ trace). I use prestateTracer to identify the slots of interest, then structLogs to get execution order and preimages.

For very large transactions, I fall back to a custom JS tracer that captures only SHA3 operations, keeping the response under 100KB instead of gigabytes.

Handling DELEGATECALL

When contract A delegatecalls contract B, B’s code executes but writes to A’s storage. Getting the correct address attribution requires care.

structLogs doesn’t include an address field on each step, so I track a call stack manually. For DELEGATECALL, storage stays with the caller while only the code context changes. For regular CALL, both change. This lets me attribute each SSTORE to the correct contract.

The prestateTracer serves as validation. It knows exactly which slots changed in which contract, so I can cross-check my attribution.

Resolving Mapping Keys

The SHA3 preimage capture mentioned above deserves a deeper look. Mapping slots are computed as keccak256(key || baseSlot). For balances[0xABC...] at slot 5, the EVM hashes the address concatenated with the slot number to produce the final storage location:

| Step | Value |

|---|---|

| Variable | mapping(address => uint256) balances at slot 5 |

| Key | 0xABC...123 |

| Hash Input | 0xABC...123 ‖ 0x05 (64 bytes total) |

| Final Slot | keccak256(input) → 0x8a3f7b2c9d... |

The Reverse Engineering Problem

When digging through trace data, this final slot is all we see. Since hashes are one-way functions, given just the slot hash, the key used to compute it is not recoverable through computation alone.

When I see an SSTORE to slot 0x8a3f7b2c9d..., I need to figure out which mapping key produced that hash. I can’t reverse the hash itself.

The Solution: Capturing Preimages at Runtime

The EVM has to compute these hashes at runtime. If I’m tracing execution, I can capture them as they happen.

When the EVM executes SHA3, I grab:

- The memory region being hashed (the preimage, containing the key and base slot)

- The resulting hash (from the next step’s stack)

This gives me a lookup table: hash → preimage. When I see an SSTORE to a hashed slot, I check the table. The key that produced that hash is right there.

The Compile-Time Optimization Problem

This approach works well, until it doesn’t. I hit a case with no SHA3 in the trace. The slot was clearly a mapping (huge hash value), but no preimage to be found.

The culprit: compile-time optimization.

address constant REWARD_TOKEN = 0xD533a949740bb3306d119CC777fa900bA034cd52;

mapping(address => uint256) rewards;

function setReward() external {

rewards[REWARD_TOKEN] = 100; // No runtime SHA3!

}

There are some cases when No preceding SHA3 opcode can be found! This is a result of optimization-time logic where the compiler sees a constant used as a mapping key, it pre-computes the hash and embeds it in bytecode. At runtime: CODECOPY → SSTORE. This is a nice gas savings trick by the compiler which forces us to handle a new edge case.

My solution: parse the source code for constant addresses and pre-compute their mapping hashes myself. If runtime capture fails, the source-derived lookup fills the gap.

Decoding Storage Patterns

Solidity hides a surprising amount of complexity inside 32-byte slots. Here are the patterns you must handle to correctly decode storage.

Packed Variables

Variables smaller than 32 bytes can share a slot. An address (20 bytes) + bool (1 byte) + uint32 (4 bytes) all fit in one slot.

This means a single storage write can change multiple variables. You can’t just decode “the value that changed.” You need to decode the entire slot into its component parts, using the layout’s offset and size information for each variable.

Dynamic Strings

Solidity’s string encoding has a quirk that tripped me up.

Short strings (< 32 bytes) store content and length in the same slot. The lowest byte holds length * 2.

Long strings (>= 32 bytes) work completely differently. The base slot stores length * 2 + 1. The actual content lives at keccak256(baseSlot), potentially spanning multiple consecutive slots.

You have to detect which encoding is in use before decoding. I check the lowest bit of the base slot value: if it’s set, it’s a long string.

Nested Mappings and Arrays of Structs

These compound types are where slot resolution gets genuinely complex.

For mapping(address => mapping(uint256 => Data)):

- Outer lookup:

keccak256(outerKey || baseSlot)→ intermediate slot - Inner lookup:

keccak256(innerKey || intermediateSlot)→ final slot

You need to chain preimage lookups to recover both keys.

Dynamic arrays of structs add another dimension:

- Length stored at base slot

- Data starts at

keccak256(baseSlot) - Element N lives at

dataStart + N * slotsPerElement - Individual struct fields offset within each element

When I see a write to slot 0x8f3a..., I might need to trace back through several layers: “this is offset 2 within element 7 of the proposals array, which means it’s the votesFor field.”

Proxy Detection

Proxies break naïve storage decoders because the layout belongs to the implementation, not the proxy. The contract you’re looking at isn’t the contract with the logic.

Three Proxy Patterns

EIP-1167 minimal proxies embed the implementation address directly in bytecode. The pattern 363d3d373d3d3d363d73 followed by 20 bytes is the address. No storage read needed.

EIP-1967 proxies store the implementation at a standard slot: 0x360894a13ba1a3210667c828492db98dca3e2076cc3735a920a3ca505d382bbc. Read that slot, get the implementation.

EIP-1822 (older UUPS) uses a different slot: 0xc5f16f0fcc639fa48a6947836d9850f504798523bf8c9a3a87d5876cf622bcf7.

The Bytecode Cache Trap

I initially tried caching storage layouts by bytecode hash. Same bytecode, same layout, right?

Wrong. For proxies.

EIP-1167 minimal proxies work because the implementation address is in the bytecode. Same bytecode means same implementation means same layout.

But EIP-1967 and EIP-1822 proxies all share identical bytecode. The implementation address is in storage, not bytecode. Different instances point to different implementations with different layouts.

I now only use bytecode caching for non-proxies and EIP-1167 minimal proxies.

Storage Layouts: Where They Come From

Storage layouts don’t exist on-chain. They’re a compile-time artifact.

The EVM only knows about 32-byte slots and 32-byte values. Variable names, types, and struct members exist only in compiler metadata that lives off-chain.

This means you need verified source code to decode storage meaningfully. But not all “verified” contracts are equal.

Sourcify stores full compiler metadata, including storage layouts when available. Usually Solidity only.

Etherscan stores source code but typically not the layout. Many contracts require local recompilation just to understand their storage.

And recompilation is fragile. Use the wrong compiler version and you get different slot assignments. Miss an optimizer setting and the packing changes. Target the wrong contract in a multi-file project and you get someone else’s layout entirely.

Exact reproduction of compiler settings isn’t optional. It’s the difference between correct decoding and complete nonsense.

Edge Cases

Constructor Storage

Contract creation transactions need special handling. The EVM knows the new contract’s address during constructor execution, but the trace data doesn’t include it. Every SSTORE during the constructor is missing its target address, so we need to reverse engineer the attribution.

The sequence:

- CREATE/CREATE2 opcode executes

- Constructor (initcode) runs, SSTOREs occur

- Trace data omits the contract address on these operations

- Created address appears on the stack only when the frame returns

I handle this by scanning for CREATE/CREATE2 opcodes, then tracking when the call depth returns to the parent level. At that point, the created address appears on the stack. I map which step ranges belong to each constructor so I can retroactively attribute those SSTOREs to the correct contract.

Vyper Differences

Vyper uses different type names (HashMap instead of mapping), different packing rules, and importantly, doesn’t include storage layouts in standard compilation output. I had to use an experimental compiler flag to get layout information.

String encoding differs too. Vyper stores length as raw byte count, not Solidity’s length * 2 + 1 encoding. The decoder needs to know which compiler produced the contract.

Key Takeaways

The compiler is the source of truth. Without exact compiler metadata, storage decoding is guesswork.

Multiple trace passes are necessary. prestateTracer gives you ground truth for what changed; structLogs gives you execution order and SHA3 preimages. Neither alone is sufficient.

Optimizations create blind spots. Compile-time hash precomputation breaks naive trace analysis. If your tool relies on runtime behavior, watch out for compile-time shortcuts.

Storage is more complex than it looks. Packed variables, dynamic encoding, nested structures. The simple cases are simple, but the edge cases compound.

What I Built

I built SlotScan, a tool that applies these techniques to make EVM storage readable.

Paste any verified contract address to see its full storage layout with decoded values. Enter a transaction hash to see exactly what storage changed, with before/after values and variable names.

Closing

The techniques here (SHA3 preimage capture, call stack tracking, multi-pass tracing) apply to any EVM storage analysis tool. The patterns are consistent across Solidity and Vyper, mainnet and L2s.

If you’re building something similar: capture SHA3 preimages, parse source for constants when runtime fails, track the call stack for DELEGATECALL, and don’t cache layouts for upgradeable proxies.

SlotScan is available at slotscan.info. The unexpected complexity of EVM storage turned a weekend project into something much deeper. Hopefully these notes help others navigating the same terrain.